Unprojectable: Projection and Perspective July 2008

Tony Conrad

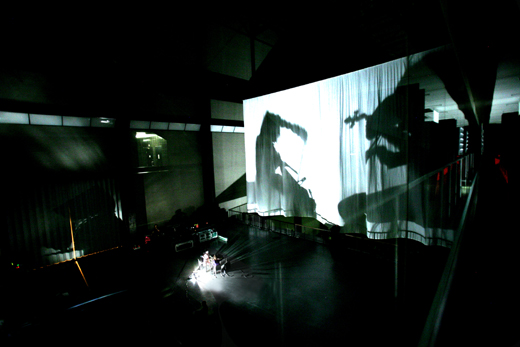

Unprojectable: Projection and Perspective, a new commission in which Conrad addresses the immense space of Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall with its central bridge as a stage, exposes us to his most recent exploration of projection and long duration on a major scale. A tremendous sound will fill the Turbine Hall, starting off with a buzzing pulse at 25 per second, mixed with an amplified string quartet including Conrad on violin, an electric drill and hand-held phonograph arms. Billowing scrims on either side of the bridge function as projection screens for the performative activities enacted behind them. These actions will include the live music performance and re-enactments of alternative film production processes Conrad developed in the mid-1970s, such as drilling holes in raw film stock. While the audience occupies the floor below, Conrad’s back-projected, larger-than-life silhouette will loom large, swaying in response to the production of sounds which will generate a pressure-filled auditory environment. The intensity of the sound will ground the event in the physical and perceptual space of the present, while the shadows might be read as a comment on the status of the present versus the re-presented and non-recoverable past in the archive of musical and visual culture.

Our audio player is currently undergoing an upgrade. Apologies for the temporary break in service. Please return in December to access this media.

Preview an excerpt from Unprojectable: Projection and Perspective © Tony Conrad

Subscribe to the Infrequency Podcasts to download the entire performance

Tony Conrad is a pivotal, polymath figure in contemporary culture, a pioneering composer, musician, performer and filmmaker, whose work emerged at the heart of New York’s fervent avant-garde art community in the early 1960s. Best known for his influential early musical explorations and the ‘experiential excess’ of his groundbreaking ‘structural film’, The Flicker, Conrad’s work offers a complex reassessment of duration and temporality, and a direct implication of the viewer as an active participant in his work. His hybrid, often perceptually intense practice has persistently expanded disciplinary boundaries and challenged traditional notions of authorship and authority for more than forty years.

After studying mathematics at Harvard, during the early 1960s Conrad developed a distinct approach to sound in contemporary musical production, introducing sustained drones built upon a strategy of minimal reduction and temporal expansion. From 1962 he was a key member of the groundbreaking Theatre of Eternal Music (also known as The Dream Syndicate). The group developed ‘Dream Music’ which dispensed with written scores and critiqued the history of western orchestral performance. Utilising long durations, precise pitch and blistering volume, its members – including Conrad, La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela and future Velvet Underground co-founders John Cale and Angus MacLise – forged a performance collaboration which denied the activity of composition, examined the physical elements of sound, and established a principal branch of the minimalist tradition. Following the dissolution of the group in 1965, Conrad has continued to reflect on duration as a concept in various fields conventionally distinguished as music, film, performance and the visual arts, always challenging his audience in whatever medium he employs.

Throughout his career Conrad has sought ‘physiological and psychological phenomena’ that produce a profound interaction with the audience. The stroboscopic, psychedelic intensity of films like The Flicker and the saturated energy and long duration of Conrad’s music can become powerful, moving and unsettling experiences that heighten awareness both of the physical experience of the event and of one’s own subjectivity within it. Carrying over from one medium to another, Conrad sets up situations that encourage free experiences of audiovisual perception and perceptual engagement, ‘manufacturing the culture as the event proceeds, as the context sustains.’

Much of Conrad’s work has involved collaboration, from the Theatre of Eternal Music to his involvement with the philosopher, musician and anti-art activist Henry Flynt, his early creative partnership with the underground artist and filmmaker Jack Smith, his participation in the influential Department of Media Study at the State University of New York at Buffalo, and more recent projects with artists such as Mike Kelley and Tony Oursler. As his career has shifted and intersected with these diverse artists, agendas and positions, Conrad has problematised not only his own work but the conventional set of categories used to contain and define it. A reconsideration of his practice also problematises traditional linear histories of the movements and developments with which he has been associated: minimalism, Fluxus, early conceptualism, underground and structural film, paracinema or expanded cinema, performance and video. The heterogeneous nature of Conrad’s work comprises a radical and productive inconsistency that continues to subvert the power structures that regulate the writing of history.

Conrad’s approach to cinema reflects his penchant for transcending boundaries and reconfiguring conventional notions of production. The Flicker, his rallying call for a new age of cinema, led the philosopher Gilles Deleuze to muse on a ‘cinema of expansion without camera, and also without screen or film stock,’ a cinema in which ‘anything can be used as a screen, the body of a protagonist or even the bodies of the spectators; anything can replace the film stock, in a virtual film which now only goes on in the head, behind the pupils.’ Conrad’s films do not rely only on luminous, audiovisual stimulation and extreme perceptual states. He has also explored a wide range of unusual materials and production methods, experimenting with various ways of cooking film – treating raw film stock as an ingredient to be stir-fried or pickled, and then projected. He has also played film as a musical instrument, stretched taut and played upon with a bow, and has used a Tesla coil to electrocute film stock.

This theatrical, performative approach to creating films makes process and production an integral and evident part of the work. The relationships between process, projection and performance have a long history within Conrad’s work and take on particular resonance in Early Minimalism, a series of compositions which refer to and redress the artist’s history with the Theatre of Eternal Music. Performances take place behind a scrim, backlit to create shadows of the performers, a spectral doubling to complicate the work’s relationship to the past.

Stuart Comer and Alice Koegel 2008

Also read / view

Infrequency PodcastsAn ongoing podcast series of live performance recordings and artist commissions