Giorgio de Chirico

The Uncertainty of the Poet

Transcript

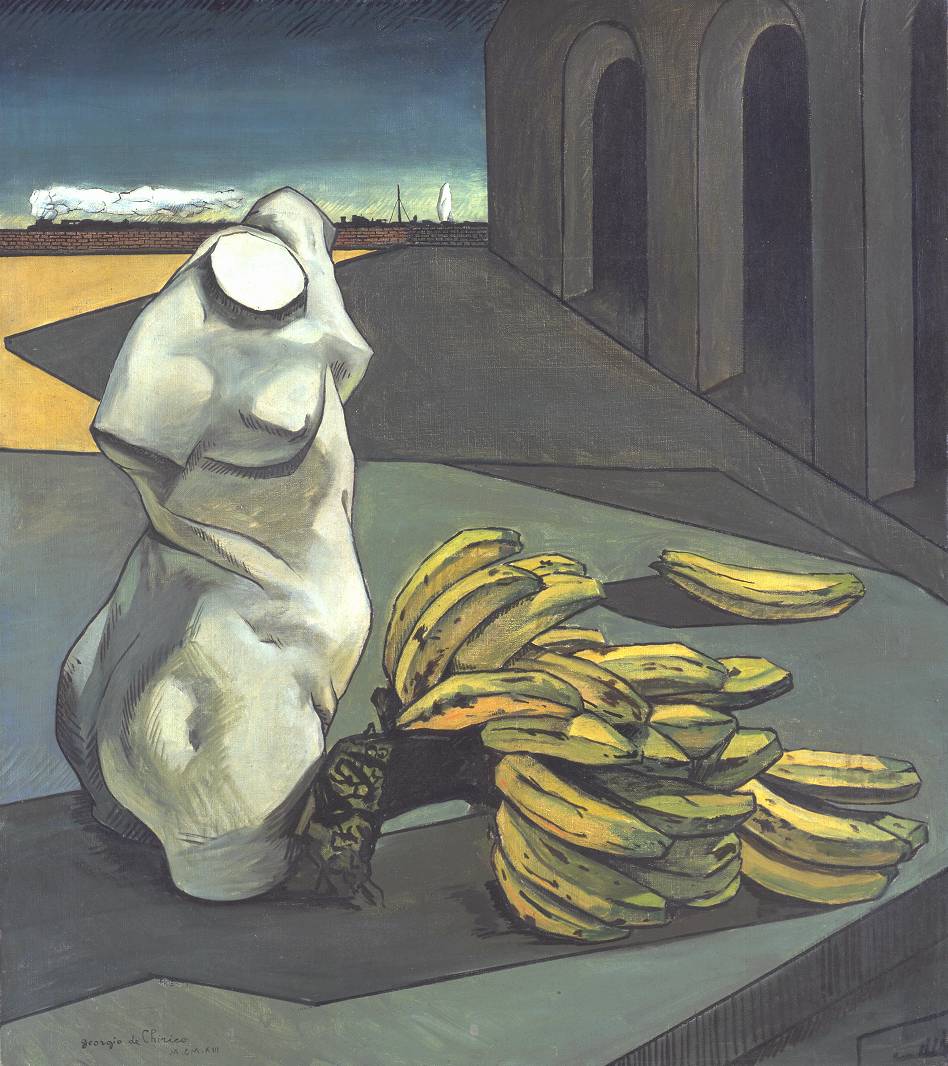

This strange and mysterious oil painting measures 106 x 94 cm. At first the scene seems naturalistic, but almost immediately the curious collection of elements within it and the exaggerated viewpoints generate a feeling of unease. The painting shows a city square entirely empty of people. In the foreground on the left is a marble statue of a female torso and lying next to it on the right are several bunches of ripe bananas still attached to a large branch. The torso is basically seen from the side, although it is twisting towards us at the waist, showing more of the chest and suggesting that the original pose might have been one of action. It has no arms below the upper bicep, no legs below the top of the thigh and no head. The statue and the bananas appear to be sitting on a gigantic plinth that fills the bottom half the painting and most of the square. On the right of the painting, cast in shadow, is a colonnade running at a sharp angle away from the viewer towards the centre of the picture. It has three arches, and the recesses beyond them darken dramatically to pitch black.

A quarter of the way down from the top of the painting is a brick wall, running horizontally across the canvas and forming a rigid horizon line. Visible just behind the wall, a steam train travels from right to left. Seen in silhouette against what appears to be an evening sky, the train ends just short of the left hand edge of the painting. Emerging from its chimney is a long plume of white smoke drifting above the roofs of its carriages.

De Chirico was only twenty-five when he painted The Uncertainty of the Poet. He had arrived in Paris the year before having spent much of the previous six years travelling. He was born in Athens but left Greece with his mother and brother when he was seventeen after his father died. In the intervening years, De Chirico had travelled to Venice, Florence, Turin and Milan and studied art for three years in Munich. During this time he developed a style that came to be known as Metaphysical painting. Metaphysics in Christian theology means the world after death, but for De Chirico it meant the otherworldly, the imagined and the enigmatic.

He said that, "one must picture everything in the world as an enigma…To live in the world as if in an immense museum of strangeness, full of curious many-coloured toys which change their appearance, which like little children we sometimes break to see how they are made on the inside."

Unlike the Italian Futurists who despised the art of the past and strove to create works of art that celebrated modernity and speed, De Chirico’s Metaphysical paintings feel eerily still and are filled with references to Europe’s classical past such as ancient Greek statuary and Renaissance architecture. His style was the product of the unique combination of influences he had acquired during his travels as a young man. In Munich, he was fascinated by the Symbolist artists Max Klinger and Arnold Bocklin whose paintings featured strange narratives and mythical creatures. He was also exposed to the philosopher Nietzsche, who inspired his belief in the possibility of a reality parallel to one’s own everyday experience. His brief stay in Turin also had a lasting impact on his art. Its piazzas, colonnades and statues became the central motifs of his Metaphysical paintings. So when De Chirico finally arrived in Paris in 1912, his style was already fully formed, though it was the French critic Apollinaire who first applied the term ‘Metaphysical’ to his work.

Apollinaire was an early supporter of his work, appreciating the mysterious dream-like atmosphere the paintings evoked. Through Apollinaire, De Chirico found a dealer and met leading avant-garde artists such as Picasso. But both as a painter and as a man, he preferred to keep himself to himself. During World War I he went back to Italy and on his return to Paris in 1924 he had radically changed his approach to painting, rejecting his Metaphysical works. However, those pre-war paintings now attracted the attention of the Surrealists who saw in them strong connections with their own interest in the unconscious mind and Freud’s analysis of dreams. The Surrealist’s leader Andre Breton saw De Chirico as a pre-cursor to the Surrealist movement and though the group never embraced his post-war style, De Chirico’s art was to have a huge influence on the work of Max Ernst, Salvador Dali and Magritte.

The Uncertainty of the Poet is framed on two sides by architecture. On the right of the painting is a colonnade made up of three immensely tall arches decreasing in height as they stretch into the distance. Only the furthest arch can be seen in its entirety since the others are cut off prematurely by the top of the painting. The width of arch nearest us is also interrupted by the vertical edge of the canvas, giving the sense that the colonnade continues beyond the painting behind us.

Particularly in Southern Europe, colonnades usually provide a cool and sheltered walkway around the edge of a building. On closer inspection however, de Chirico’s colonnade seems less than typical. As we look at its most distant point it appears that it has no building above it. And instead of being a light, airy construction, the interior is completely dark. The external surface of the colonnade is also in dark shadow, so the overall impression is of a rather threatening, sinister piece of architecture.

Through the gloom, we can see that the stonework is smooth as if it has been plastered and the columns are not rounded but square. De Chirico has emphasised the geometry of the architecture by drawing sharp black outlines along the edges of each facet of the colonnade, even demarcating the angle along which the columns meet the ground as if it were a wall meeting a floor. This gives the colonnade an unnatural and aggressive perspectival accuracy.

If the colonnade forms a wall along the right of the painting, then the brick wall forms one at the back. Like the colonnade, De Chirico has drawn a bold black line along the bottom of the wall marking the point at which it meets the ground. These emphatic black lines almost seem like an attempt to confine us to the piazza, preventing us from escaping back to our own reality. The effect is both claustrophobic and alienating. As viewers, we seem to be utterly alone in what should be a crowded public space. The emptiness and feeling of silence in this painting is so intense that one doubts whether there are even people on the speeding train beyond the wall.

Despite the fact that the wall is in the far distance, De Chirico has marked each red brick individually in its surrounding dark cement. For each brick to be visible at this distance they would have to be enormous. As such, these unrealistically sized bricks also play with our sense scale. It becomes impossible to judge the size of the wall in relation to the train, as they seem to be operating in different dimensions altogether. If the bricks are a standard size, then the steam engine has been miniaturised. Alternatively, if the train is to scale the bricks have to be monumental.

Soon, other strange features become noticeable along the line of the wall. For instance, towards its right hand end is what appears to be a plume of white smoke rising from some hidden location. We know the train has not produced it, because the smoke from the train’s chimney has been shaped into a fat horizontal cloud by its forward motion. This cloud of smoke on the other hand, appears to rise from its unknown source in an undisturbed vertical column, indicating that the air is still and windless and adding to our sense of claustrophobia.

To the left of the smoke De Chirico provides another suggestion of an existence beyond the piazza, as partially obscured by the wall is what appears to be the mast and rigging of a sailing boat.

For De Chirico, trains were a metaphor for the journey into the unconscious mind. It is also likely that they held a personal significance, since his father was a railway engineer. However, in this work neither train nor boat seems to offer an escape from the stifling and eerie world of the painting.

The harsh geometry of the wall and the colonnade is enhanced by the stone plinth beneath the statue and the bananas. Plinths are flat bases upon which a sculpture sits and as such, are usually slightly larger that the base area of the sculpture. Not only is this plinth enormous, it also has a very strange shape, unrelated to the objects its supports. It fills the bottom half of the painting, emerging from the left of the picture and stopping just short of the colonnade on the right hand side. In the bottom right hand corner of the painting we can also glimpse the near edge of the plinth.

Its surface is smooth and a murky grey-green in colour, giving it the appearance of slate. The paint has been applied quite thinly, so in places the lower layer of mustard yellow shows through, while across the surface of the plinth individual brush strokes are visible in the paint. The near edge of the plinth reveals that its probably several centimetres thick. This solidity combined with the smooth surface, makes the plinth resemble the lid of a tomb.

A dark, crisp shadow cuts across the top right hand corner of the plinth, part of a larger shadow thrown by the colonnade across most of the piazza. Its presence is heavy and emphatic, but its shape it does not seem to correspond with the shape of the colonnade.

The only part of the piazza not cast in shadow is a chevron shaped patch of ground painted bright mustard yellow. Compared to the darkness of the shadowed building, the stone plinth, the red brick wall and the black steam train, this patch of yellow appears very vivid and implies that the sunlight is strong and hot. This sense of Mediterranean heat is reinforced by the deep blue sky above the train that runs from dark azure blue at the top of the painting to a more golden hue as it disappears behind the wall.

The yellow paint describing this sunny part of the piazza had been laid on the canvas smoothly, without any attempt at describing texture. Since other textures in the painting seem naturalistic, the viewer’s instinct is to read this yellow surface as sand. However, this is a curious surface for a public square and more reminiscent of a bullring.

The bright yellow in the piazza is repeated in the large pile of bananas lying in the foreground. Twenty-three bananas hang from the branch in an enormous bunch, the shape of which echoes the narrowing V-shape of the plinth on which they sit. Like the architecture, the facets of the bananas have been emphasised so that they look chiselled rather than soft. We can see that the fruit is ripe, as lines of brown discolouration appear along their edges and in patches across the yellow skin. In places the underside of the bananas reflect the green-grey colour of the plinth. This gives some of them the curious impression of being both ripe and unripe at the same time. Slightly incongruously, one banana lies separate from the bunch in the top right corner of the plinth.

The scale of all of the elements in the painting is ambiguous, each object refusing to act as a reliable guide to the size of any other. If we use the bananas as our standard, the statue appears to be somewhat less than lifesize. But equally, we might choose the statue itself as a gauge, in which case De Chirico is presenting us with an oversize bunch of bananas.

The sculpted female torso is positioned so that her hips face slightly away from us and towards the colonnade. Her body is then twisted sharply towards us at the waist as if she were trying to look over her right shoulder at the ground behind her. This means that we can see both her buttocks, as well as her breasts in three quarter profile which, although unnatural, is dramatic in this otherwise actionless scene.

Despite its lack of head and limbs, the statue is as close as we come to a human presence in the picture. De Chirico enjoyed the way sculpture could capture in cold, lifeless stone a sense of the life and energy of its subjects, long after the subject itself had passed on. In other paintings from this period his city squares include the statue of Ariadne, who in Greek mythology helped Theseus escape from the labyrinth and the Minotaur.

However, if this is Ariadne, her dismembered body offers little hope of escape from this scene. Her lifeless permanence however, does draw our attention to the gradual decay of the bananas next to her, the only objects in the piazza which do not seem immune to the passing of time.

Although the surface of the marble is smooth, De Chirico has used hatched lines to describe the shadows around the curves of the torso. These dark, forceful lines are consistent with De Chirico’s mark-making elsewhere in painting, but here they also seem to mimic the impressions left by a sculptor’s chisel.

The shadow cast by the bananas and the statue has only a passing relationship with the forms that create it. Like the shadow of the colonnade, it is a severe geometric shape, creating a zigzag beneath the fruit and the sculpture. By depicting the shadow at all, De Chirico appears to be adhering some sense of naturalism. But by depicting it in this way, oddly unrelated to the objects above it, he shatters the illusion in the same gesture.